Introduction

On November 29, 2023, a judgment from the Beijing Internet Court ignited the legal community.

Finally, the first court decision on the copyright ownership and infringement determination of “AI-generated art” works was issued in China.

I meticulously examined the document promptly upon its release.

However, I hold certain dissenting opinions regarding the judge’s determinations.

The judge asserts that as long as the generation of a work involves aspects such as “the presentation of designed characters, the selection of prompting words, the arrangement of the order of prompting words, the setting of relevant parameters, and the selection of which image meets expectations,” it constitutes a requirement for “intellectual achievement.” Consequently, users can possess the copyright to the outputted work.

For those familiar with the principles of AI and Stable Diffusion software, one can deduce from this judgment a potential reality:

In the future, those with sufficient computing power, can monopolize the copyright to AI-generated artistic works in China.

Diverging from peers who analyze solely based on the judgment, I will attempt a technical analysis, hoping to provide you with a different perspective and experience.

* This article represents the author’s personal opinions and should not be considered as legal advice or opinions.

**Special thanks to “知产库” for sharing the judgment.

I. Summary of the Judgment

I believe many readers have either read or heard about the content of the judgment. To facilitate the subsequent reading, I will provide a simple summary of the judgment.

Case Overview:

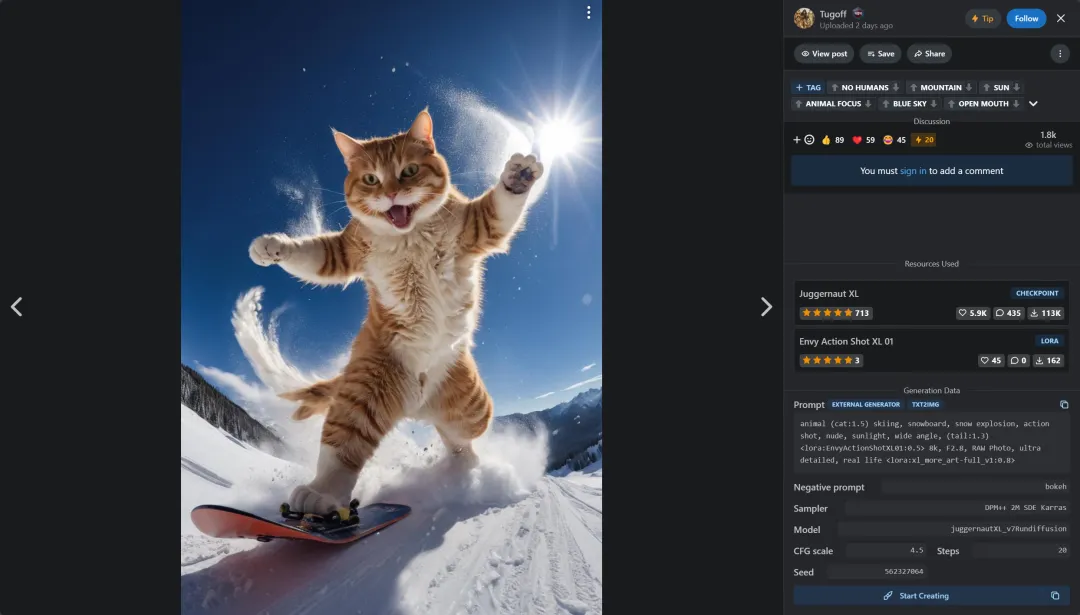

The plaintiff, Mr. Li, used Stable Diffusion software (an AI drawing tool) to generate the relevant image, which he then published on the Xiaohongshu platform.

The defendant, Mr. Liu, a Baidu Baijiahao blogger, without obtaining permission from the plaintiff and by cropping out the plaintiff’s signature watermark on the Xiaohongshu platform, used the AI-generated image in his blog post, leading users to mistakenly believe that the defendant was the author of the work.

Upon discovering this, the plaintiff filed a lawsuit with the Beijing Internet Court. The lawsuit requests:

- A court order directing the defendant to issue a public statement on the Baijiahao platform apologizing to the plaintiff, eliminating the impact of his infringement on the plaintiff;

- A court order directing the defendant to compensate the plaintiff for economic losses amounting to 5000 yuan.

During the trial, the plaintiff also demonstrated how to reproduce the process of creating the AI-generated image step by step using Stable Diffusion software.

Court Findings:

1. Whether the Contested Image Constitutes a Work and What Type of Work

Regarding “Intellectual Achievement”:

From the plaintiff’s conception of the contested image to the final selection of the image, the entire process involves a certain level of intellectual input, such as designing the presentation of characters, selecting prompting words, arranging the order of prompting words, setting relevant parameters, and choosing which image meets expectations. The contested image reflects the plaintiff’s intellectual input, fulfilling the requirement of “intellectual achievement.”

Regarding “Originality”:

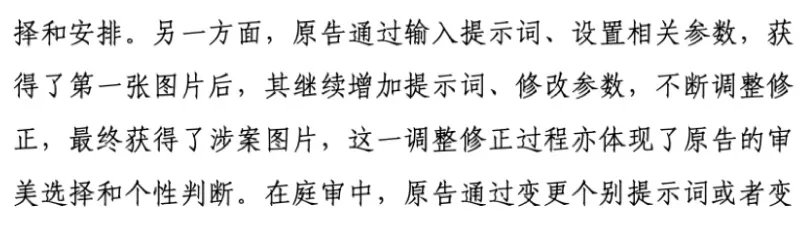

The plaintiff designed visual elements such as characters and their presentation through prompting words and set parameters for layout and composition, demonstrating the plaintiff’s choices and arrangements. Additionally, the plaintiff, through inputting prompting words and adjusting parameters, obtained the initial image, continued to add prompting words, modified parameters, and continuously adjusted and revised, ultimately obtaining the contested image. This adjustment and revision process also reflect the plaintiff’s aesthetic choices and personal judgment.

Therefore, the contested image is not a “mechanical intellectual achievement.” In the absence of contrary evidence, it can be concluded that the plaintiff independently completed the contested image, demonstrating the plaintiff’s personalized expression. In summary, the contested image meets the requirement of “originality.”

Regarding Whether It Belongs to “Mechanical Intellectual Achievement”:

The plaintiff generated different images by changing individual prompting words or parameters, indicating that using this model for creation allows different individuals to input new prompting words and set new parameters to generate different content. Therefore, the contested image is not a “mechanical intellectual achievement.”

2. Whether the Plaintiff Has Copyright to the Contested Image

2.1 Model:

As per China’s copyright law, the term “author” is limited to natural persons, legal persons, and unincorporated organizations. Therefore, the model used to generate the contested image cannot be considered the “author.”

2.2 Artificial Intelligence Software (Author of Stable Diffusion):

Because it lacks the intention to create the contested image, did not pre-set subsequent creative content, and did not participate in the subsequent creative process, it is merely the producer of the creative tool.

2.3 Plaintiff:

The plaintiff directly set relevant parameters for the contested artificial intelligence model as needed, and is the person who ultimately selected the contested image. The contested image is directly produced based on the plaintiff’s intellectual input and reflects the plaintiff’s personalized expression. Therefore, the plaintiff is the author of the contested image and holds the copyright to it.

3. Whether the Defendant’s Actions Constitute Infringement and Whether the Defendant Should Bear Legal Responsibility

The defendant’s dissemination of the contested image constitutes an infringement of the plaintiff’s “information network dissemination right” in the work;

The defendant’s act of disseminating the contested image while removing the plaintiff’s signature constitutes an infringement of the plaintiff’s “right of attribution.”

Judgment Outcome:

- The defendant must issue an apology statement on his Baijiahao platform for at least 24 hours;

- The defendant must compensate the plaintiff for losses amounting to 500 yuan.

II. Analysis of Insufficient Basis for Copyright Determination in This Case Based on the Principle of SD Software

1. Operating Principles of Stable Diffusion Software and Its Model

I have previously discussed the algorithmic principles behind Stable Diffusion software. Interested readers can refer to ( Only Chinese now) :

In brief, the Diffusion algorithm associates materials in the training set with corresponding labeling information, enabling the algorithm model to learn this association and understand the common rules of images in the training set with the same labeling information. During training, various possibilities of simulating distributed pixel points (i.e., “paths”) are generated to meet these common rules. In the generation phase, by matching the labeling information during training with the input requirements (i.e., “prompt words”), the software searches for the generation path that best fits the image represented by this type of labeling information, ultimately generating an image that matches the prompt word content.

In the Stable Diffusion software, the parameter “seed” represents a specific “path.”

2. Using the Same “Path” Results in a Unique Outcome

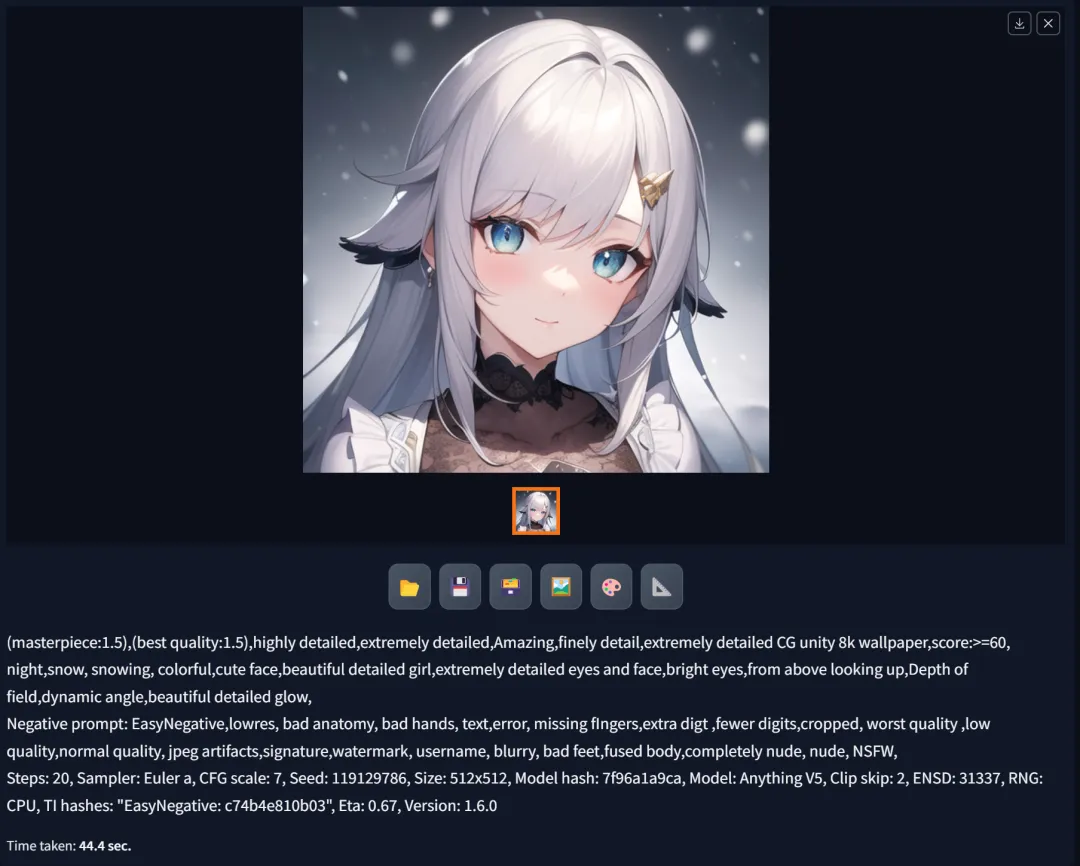

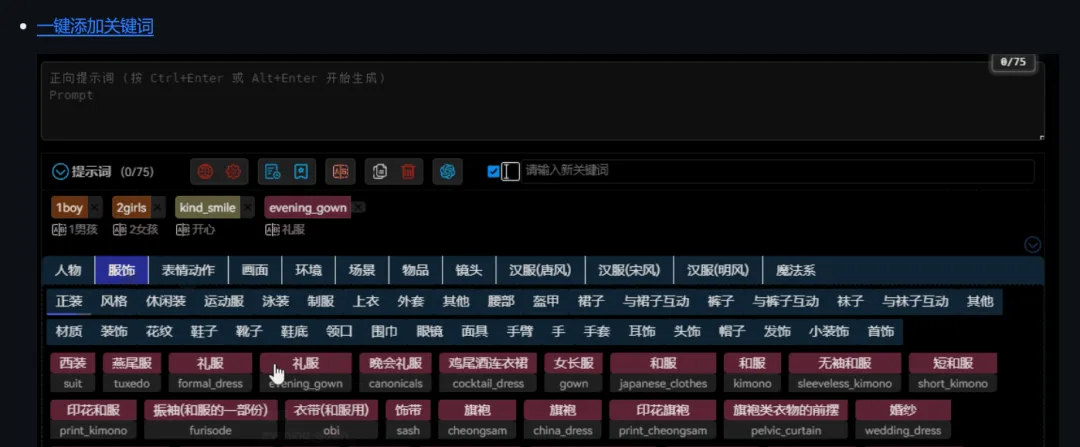

In the judgment, we learn that the plaintiff demonstrated in court the ability to regenerate the contested image by re-entering relevant positive and negative prompt words, iteration counts, LoRA model weights, and other parameters, while keeping the “seed” fixed.

This effectively implies that the contested image is, in essence, a result of “mechanical generation” based on fixed parameters.

The fact that it is “reproducible” is a key feature that sets Stable Diffusion software apart from other AI generation software (such as Midjourney, DALL·E, etc.).

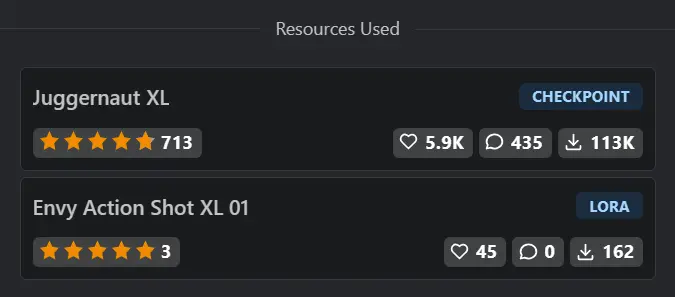

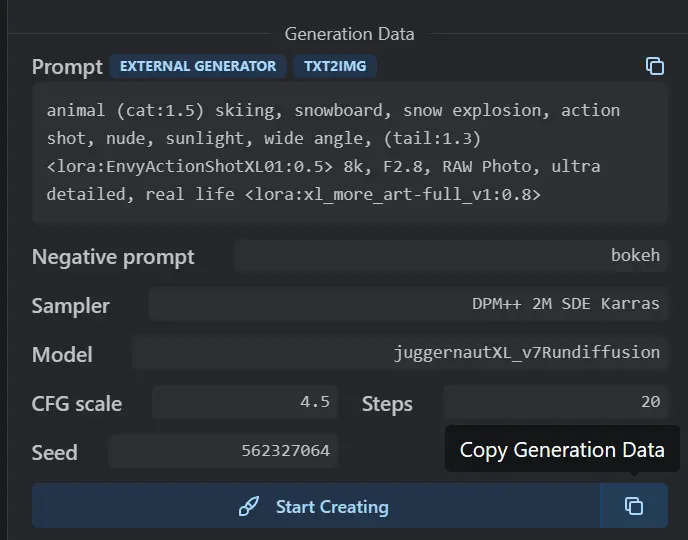

On the well-known AI model sharing platform Civitai, numerous users share AI images. These images include the specific model used (Resources) and the parameters used during generation (Generation Data). The website also provides a “one-click copy” function for parameters.

The generated parameter information that can be obtained by pressing the copy button is as follows:

animal (cat:1.5) skiing, snowboard, snow explosion, action shot, nude, sunlight, wide angle, (tail:1.3) <lora:EnvyActionShotXL01:0.5> 8k, F2.8, RAW Photo, ultra detailed, real life <lora:xl_more_art-full_v1:0.8>

Negative prompt: bokeh

Steps: 20, VAE: sdxl_vae.safetensors, Size: 832×1216, Seed: 562327064, Model: juggernautXL_v7Rundiffusion, Version: v1.6.0-2-g4afaaf8a, Sampler: DPM++ 2M SDE Karras, VAE hash: b3165c12ca, CFG scale: 4.5, Model hash: 0724518c6b, “EnvyActionShotXL01: 46f3acce826a, xl_more_art-full_v1: fe3b4816be83”

Other users simply need to download and use the same model, import the generated parameters with a single click on the software interface, to replicate this image on their own devices.

While the final outcome may not be an exact 100% replica due to factors such as computer hardware, software plugin versions, model versions, etc., the generated results are substantial enough to constitute “substantial similarity.” Below are some images tested by fellow users:

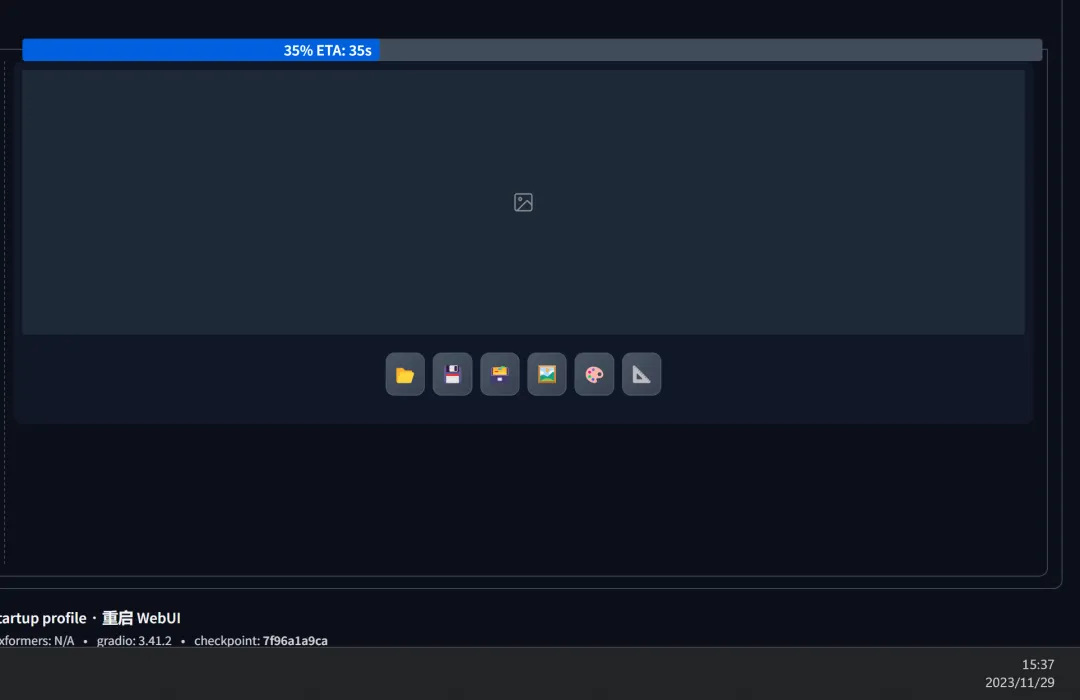

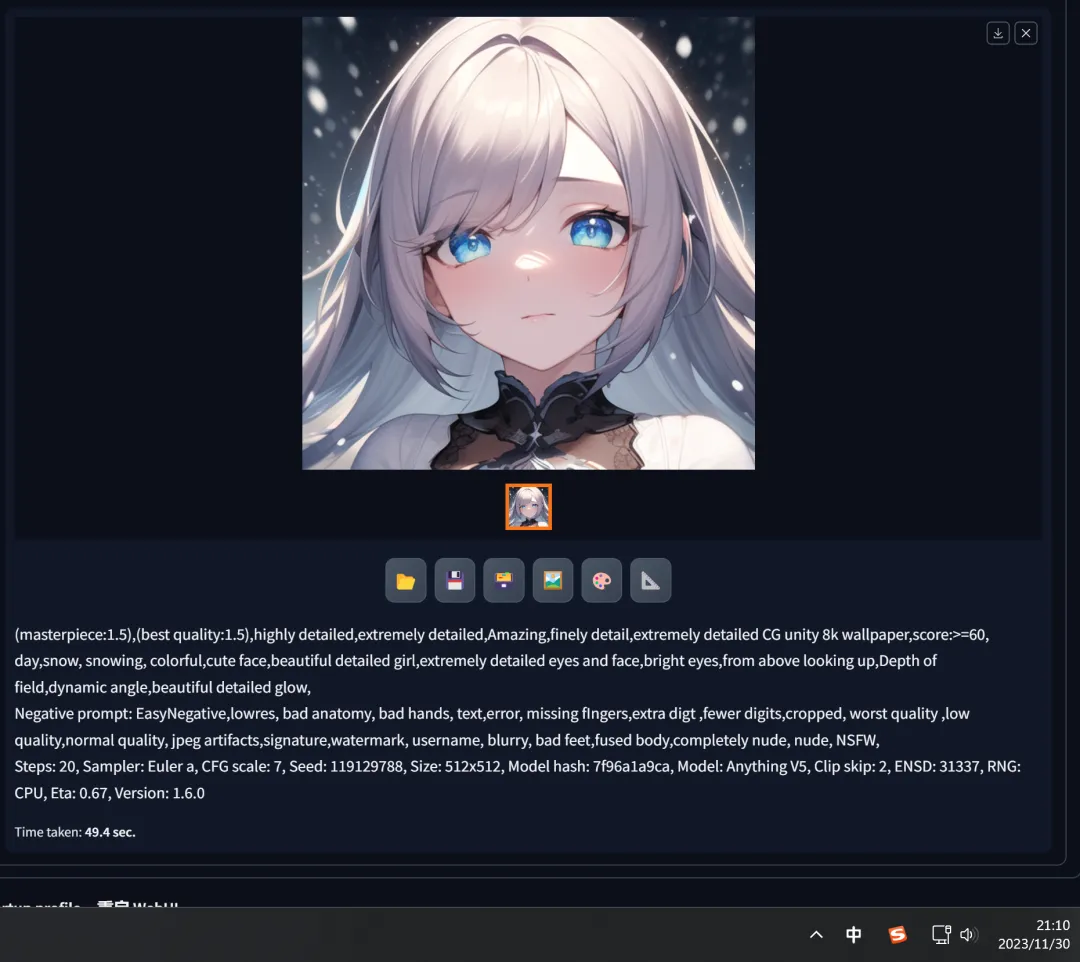

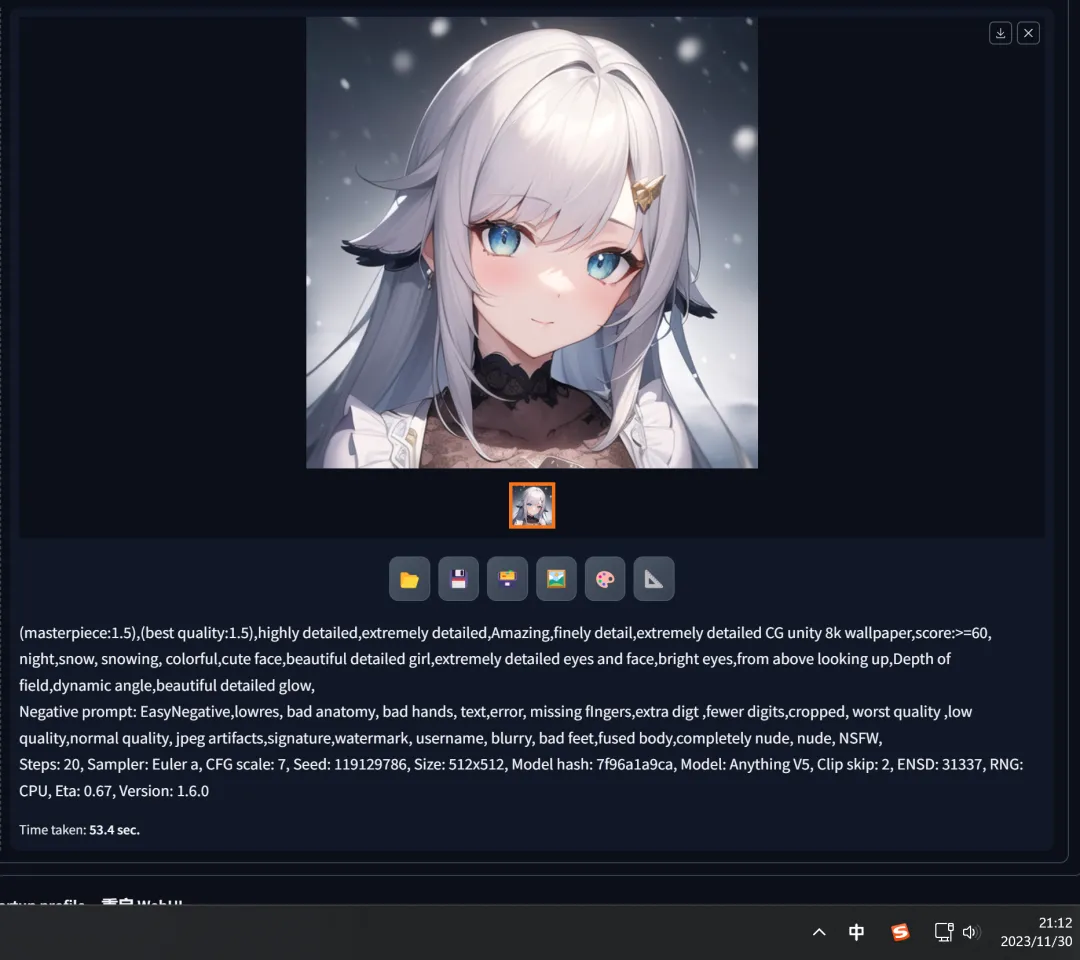

Based on the parameters recorded in the judgment, and without knowledge of the software version, plugins, hardware devices, and parameters not mentioned in the undisclosed judgment, I was able to reproduce the following results on my computer. Aside from the body, there are clear similarities in the facial features, background, and lower body clothing. The overall composition is also remarkably similar:

When there are minimal factors influencing the outcome, as in the plaintiff’s reproduction process, the result can achieve a complete 100% similarity.

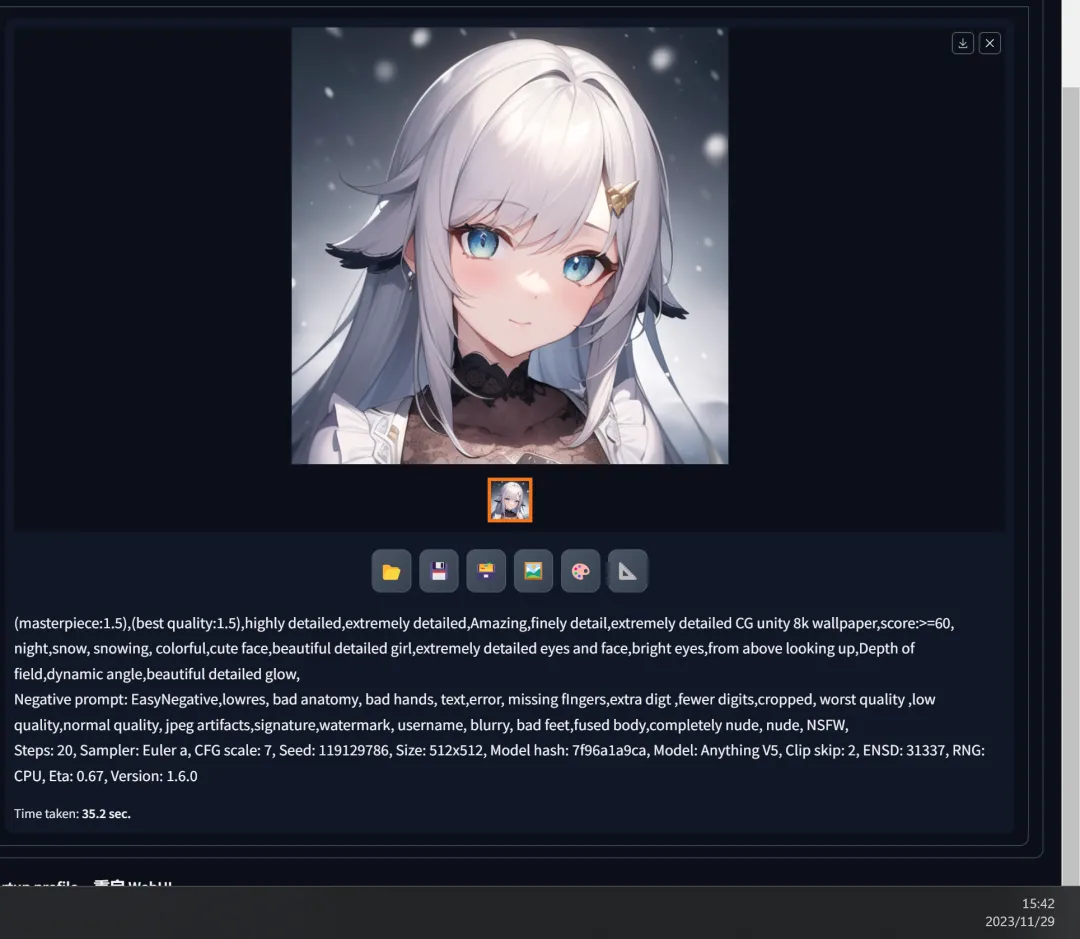

To further demonstrate, I will document a test result:

- In Stable Diffusion software, after entering all basic generation parameters, keeping the random seed at -1 (meaning a randomly generated seed, which is a normal process for generating AI images; in practice, the software is rarely used to fix the seed before adjusting parameters), click on image generation.

2. Obtaining the initial generation result and its seed parameters:

3. Restarting the software, entering the same parameters again, and modifying the seed parameter to match the result of the second step, then clicking on generation:

4. The exact same image was obtained:

It is evident that, under the conditions of using the same model and generation parameters, with identical “seed parameters,” the generated images can achieve “substantial similarity” or even identical results.

3. AI-Generated Images are Merely “Mechanical Intellectual Achievements” Calculated in a Certain Way

Both the plaintiff’s demonstrated reproduction process in the case and the results of the test conducted earlier point to a common fact:

The so-called “AI art” is merely a process where, amidst an enormous number of possibilities generated during model training, calculations are performed based on the algorithm’s formulas and input parameters. This process leads to a specific result and generates the corresponding image.

The various adjustments made by the plaintiff during the reproduction process are fundamentally unrelated to the final result. The process of adjusting parameters merely points to different generated results of the model. As long as the final input parameters match those used to generate the image, regardless of the numerous adjustments made earlier, the final result remains unchanged, much like the fixed and accurate result of 1+1=2 in a common setting.

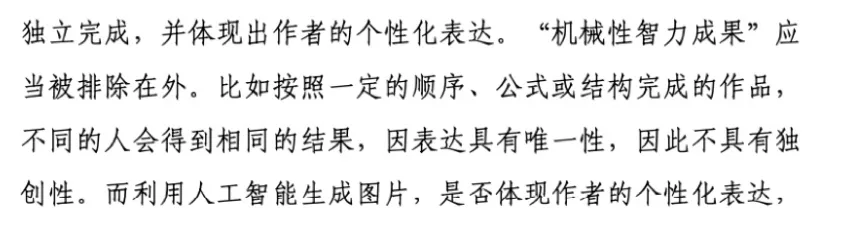

As expressed in the judgment regarding “mechanical intellectual achievements“:

“Mechanical intellectual achievements” should be excluded. For instance, works completed according to a specific order, formula, or structure where different individuals obtain identical results lack originality due to their predetermined and unique expression.

Regardless of the creator, as long as the same model is selected on the same device, and parameters are input in a specific order, the AI image generated by pressing the mouse button will be identical. It has no relation to the person pressing the button, the time, or the location.

At least in the current stage, “AI-generated images” are merely “mechanical intellectual achievements.”

4. We’re Just “Picking Monkey Selfies”

In this case, the judge considered that the plaintiff’s process of adjusting and modifying parameters reflected the plaintiff’s aesthetic choices and personal judgment.

However, as discussed above, we can now conclude that the plaintiff (and even those using AI for drawing) is simply selecting an image from a collection of “mechanical intellectual achievements” that align with human aesthetics.

The judge used the example of a “camera” in the judgment, and I would like to cite another example involving a “camera”:

In 2011, British photographer David Slater was on a photography expedition in the wilds of Indonesia. During the shoot, he fixed his camera on a tripod and intentionally left the remote shutter accessible, allowing a black macaque to approach the camera. A female macaque pressed the remote shutter, capturing a large number of photos, most of which were blurry and unusable. However, Slater selected two of the most interesting photos from the collection, which were later published on a website:

Wikipedia placed these two photos on its website, stating that they were “taken by a monkey.” This led Slater to believe that Wikipedia had infringed on his copyright. Slater sued the parent company of Wikipedia, and in December 2014, the U.S. Copyright Office determined that it was indeed “taken by a monkey” and declared that works not created by humans are not the subject of U.S. copyright. In 2016, a U.S. federal judge ruled that the monkey could not hold the copyright to these images. In 2018, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the original judgment.

If we draw parallels with the present case, the plaintiff’s actions are akin to Slater’s; both are essentially selecting an image from a pool of works not created by humans. The plaintiff’s process of adjusting parameters is simply “choosing a different gesture from a box filled with various images,” and this image fundamentally does not incorporate any element of their own “creation.”

As the colloquial term for “AI drawing” goes: “gacha,” we do not consider the process of drawing lots (even if we set parameters for potential types, colors, sizes, shapes, probabilities, etc.) as a “creative process.” Similarly, we do not regard the prizes drawn as “works” for which we hold the copyright. Consequently, we should not attribute copyright ownership to the “drawer” for the “works” extracted during “AI drawing.”

5. Even the prompt words lack the elements of “creation.”

Readers familiar with Stable Diffusion software may be aware that there are many prompt word plugins available online. Numerous users share practical prompt word templates on websites, forums, blogs, etc.

When using the LoRA model, it often requires inputting trigger prompt words; otherwise, the final generated result cannot incorporate the effects of the LoRA model.

The reason for these restrictions is that the range of prompt words that can be input and influence the generated results is directly correlated with the “labels” in the model training set.

No one can input prompt words beyond the “label” range, nor can they “create” content beyond what is already labeled within the model. Otherwise, the drawing program will be unable to understand the meaning of these prompt words, and it cannot generate elements related to these prompt words in the output results.

During the trial, the plaintiff mentioned that most of the prompt words used in their “creation” process were directly copied from other people’s templates.

Even the reverse prompt words they edited themselves did not exceed common ranges; they simply selected from existing ranges, and it was not a result of their “independent creation.“

6. Looking at the entire process of “creation,” the plaintiff does not exhibit a “creative” act and should not be entitled to copyright.

From the analysis above, we can now draw a conclusion:

The plaintiff, whether inputting parameters, adjusting parameters, or selecting generated results, is only operating within the “possibilities” that the model can provide. The image generated by AI is essentially related to the device, model, and software and has no connection to the user. Anyone using the same device, model, and software can obtain identical results across time and space. Therefore, the AI-generated image in question perfectly fits the definition of “mechanical intellectual achievement”.

When users directly use the AI-generated result, they are merely engaged in a process of selection based on human aesthetics, without any connection to the creation of the image. Their act of inputting parameters only confines the range of “possibilities” and has no correlation with the generation of the result. It lacks the essential elements of “creation” by influencing the generation result through intellectual input.

Therefore, whether analyzing the nature of the image in question or based on the plaintiff’s generation process, the plaintiff should not be entitled to the copyright of the works in question (more appropriately referred to as the “image in question”).

III. Other detailed issues in the judgment

Furthermore, there are other detailed issues in the judgment:

1. The plaintiff’s replication process does not provide conclusive evidence of their creative act.

The judgment mentions that the plaintiff’s “adjustment of parameters” demonstrated in the replication video reflects the plaintiff’s “aesthetic choices and personal judgments,” leading to the conclusion that the image in question has “originality.”

Unlike traditional electronic art data sources that contain information such as layers and operation logs, AI drawing (in the case of Stable Diffusion) only has the generated image and the accompanying generation parameter information, with no record of any “process.”

As mentioned earlier, in the case of consistent final parameters, regardless of the complexity of the debugging process shown in the “replication video,” as long as the final parameters are the same, an identical image can be generated.

Let’s illustrate this again with the example mentioned earlier in Stable Diffusion:

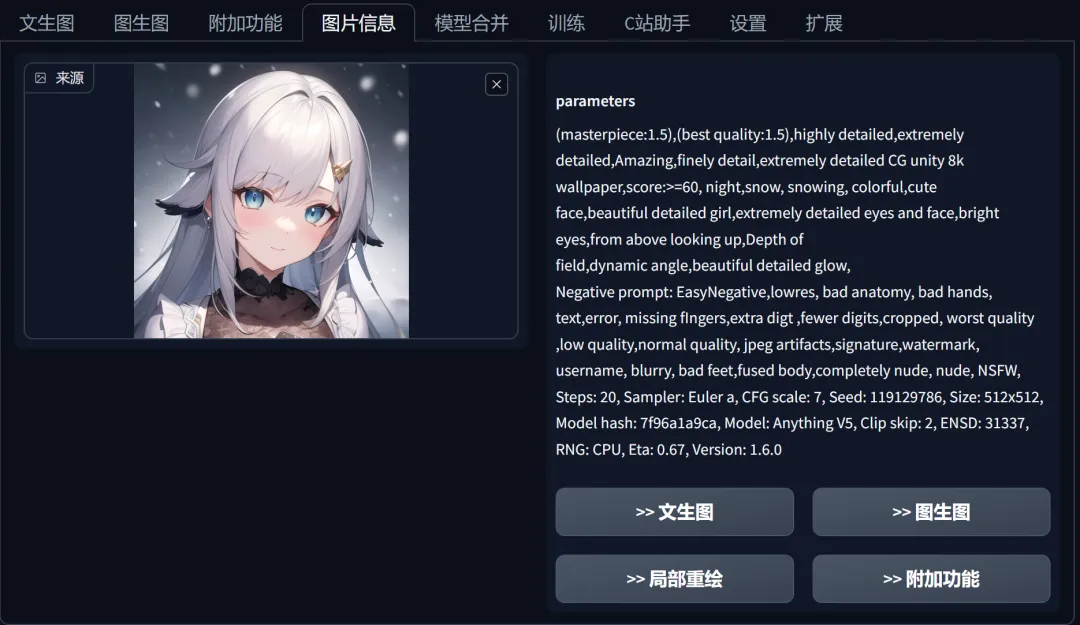

- In Stable Diffusion, without changing the seed and adjusting one key word, changing “night” to “day,” pressing the generate button results in a completely different image:

2. Then, keeping the current trigger word unchanged, modifying the “seed” to “119129788,” and pressing the generate button, resulted in another distinct image.

3. Finally, reverting the trigger word and “seed” back to the original version and pressing the generate button again demonstrated a complete “replication” of the original image.

In fact, anyone can use Stable Diffusion’s “image information” feature to retrieve the generation information of any previously generated image. By sending it to the “txt2img” function, one can readjust the parameters to obtain a different generation result. Of course, this process can also be used to replicate the same image.

While there is no evidence proving that the plaintiff engaged in a “reverse creation process,” solely in terms of “evidence,” the plaintiff’s replication video does not possess sufficient proof of the “creative process.”

2. The plaintiff’s “creative process” differs significantly from common practice.

“AI drawing” is a process akin to “drawing a card,” where the outcome is unknown. Therefore, mainstream (and the vast majority of) Stable Diffusion tutorials, as well as the typical operations of ordinary software users, involve generating a large number of different images using random seeds and then selecting an image that “conforms to human aesthetics” (based on a specific “seed”). Since we cannot predict in advance which “seed” will meet our aesthetic standards, generating various images in bulk and randomly selecting from them is the optimal solution.

However, the plaintiff’s “replication process” goes against this approach. They first fix the “seed,” then adjust the LoRA model, and finally generate the relevant image by adjusting the “seed” and trigger words.

Fixing the “seed” during generation means that only one image can be generated each time. This approach lacks clear advantages in terms of practicality and efficiency, especially when modern household computer graphics cards can generate an image in a matter of seconds. It is much more effective to select from a large batch of generated images than to “randomly input a seed.”

However, it should be noted that some individuals might genuinely adopt a similar method to generate images, or the plaintiff may have chosen this method for convenience in demonstrating the process.

My statements are made from a standpoint of “common rationality” and do not imply an assumption that the plaintiff engaged in a “reverse creative process.”

IV. Possible Impact of this Case

Assuming this case becomes a “precedent” for future related judgments, it may have the following impacts on the copyright environment in China:

1. Possible Change in the Inherent Nature of Copyright

According to Article 2 of the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China, the copyright is naturally possessed regardless of whether the work is published.

Article 2: Chinese citizens, legal persons, or other organizations, regardless of whether the works are published or not, enjoy copyright under this law.

“The Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China”

However, based on the principles of AI drawing, where the uniqueness of the result is based on the “seed,” anyone might have the “copyright” to the same or similar images. The only factor influencing the acquisition of the copyright to a particular image is the “luck” of pressing the mouse button and randomly obtaining that “seed.”

This leads to a peculiar phenomenon:

The copyright owner of a work could be anyone until a specific mouse click collapses it into a concrete result.

The copyright of a work might also belong to more than one person, as long as everyone is “lucky” enough to randomly obtain the same result.

Especially when the model is smaller, and the range of possible outcomes is limited, the likelihood of generating similar images increases. In situations where everyone generates similar images, disputes over “who is the copyright owner of this image” and “who has infringed on whose rights” may arise.

How about base on the “first-to-generate” ?

However, the characteristic of electronic data is that it is “easily modifiable“. Anyone can change the timestamp of an image by adjusting the device time, for example, by backdating it two months:

This situation makes it challenging for most people, given current technology, to confirm the true generation time of an AI-drawn work, making it difficult to determine the ownership of the copyright for that image.

How about base on the “first-to-publish” or “first-to-evidence” ?

If the determination relies on the principle of “first-to-publish” or “first-to-evidence,” it significantly disrupts the inherent right of copyright ownership in works. It turns into a situation where “whoever declares ownership first” gains the rights. This means that anyone might lose copyright to their work simply because they “published it later,” or it’s only stored on a computer hard drive or in drafts, or they’re just thinking of using it “in the next issue.”

This shifts the concept of “copyright” away from “creation equals ownership” to a scenario where potential rights holders need to fight for copyright through substantial and reliable evidence. Otherwise, they risk unjustly losing the copyright to their works.

2. It may shift copyright protection from safeguarding the “creative process” to protecting the “results”.

Traditional works typically express the creative process through the results, and protecting works essentially means safeguarding the complete creative act. This is the core idea behind copyright protection: safeguarding expression.

In AI-generated works, the creative process is based on the same workflow, and with other parameters remaining constant, a simple adjustment of the “seed” parameter often yields entirely different results.

In this case, the judge deemed the plaintiff’s “creative process” to have “unique intellectual input,” thus deserving protection. However, the question arises: what type of “creative process” should be protected?

Is it the adjustment process experienced during the generation of AI images?

Is it the parameters used to generate the final AI image (normally, the creative process does not involve considering the “seed”)?

Or is it the AI image file that the creator clicks to generate (including the final parameters with the “seed”)?

If one argues in favor of protecting the “thought process,” it implies that one person can monopolize the copyright to all possible images (all “seeds”) under that parameter, which, from a fairness perspective, is evidently impractical.

If one suggests protecting only the final results, it means that anyone can use another person’s thought process — the “unique intellectual input” identified in this case — by simply inputting a new “seed” to easily obtain a new image result with some degree of variation, making it challenging to establish infringement based on traditional legal criteria.

In traditional art, this might only involve adding a stroke, possibly without adding any meaningful “intellectual input,” yet it results in obtaining full copyright for a new work.

However, from a judicial standpoint, protecting the “results” is the most straightforward way to assess infringement. When a work removes generation information, determining infringement largely relies on “visual similarity.” In AI art, altering the similarity of the final product is ironically the least part that requires “intellectual input.”

Protecting the “parameters” might lead to overly transitional protection.

Protecting the “finished product” fundamentally does not safeguard the “thought process” but merely protects the mechanically generated result beyond human intervention.

3. The criteria for copyright determination prove challenging to apply uniformly across various AI drawing software, potentially leading to discrimination.

In the case of Stable Diffusion, which requires a certain level of technical expertise for setup, many individuals might opt for other AI drawing platforms such as Midjourney, DALL·E, and Wenxin Yiyan (文心一言), both domestic and international.

These platforms share the characteristic of not necessitating users’ attention to specific generation parameters and models. Users merely input keywords to obtain image results.

The output is entirely random, making it impossible to replicate the same image even with identical keywords. Additionally, there is no possibility of adjusting details based on a particular image; each generation is a fresh output based on the provided keywords.

When using these platforms, users’ “unique intellectual input” is noticeably lower compared to users employing Stable Diffusion since they cannot manipulate various parameters.

If the same criteria used in this case are applied, could these users also claim copyright for the generated results?

Even if these users only input a set of keywords?

If copyright protection is deemed necessary, should it safeguard the keywords or the entirely random and non-replicable generated results?

If an isolated set of keywords is considered insufficient “intellectual input,” does it mean that individuals with higher technical capabilities or those using more sophisticated software in AI drawing have more rights than others?

In traditional creative software, whether using system-provided drawing tools or advanced downloaded drawing software, creators possess the same copyright for the original images they produce.

However, in the realm of AI drawing software, deeming the input of keywords and adjustment of parameters as the sole components of creativity introduces artificial barriers and discrimination, undermining fairness.

4. This situation may lead to a monopoly of copyright by computational power.

If the current principles of copyright are not changed, based solely on the circumstances determined in this case, a disturbing conclusion can be deduced:

In the future, whoever possesses more hardware computational power will be able to generate more images faster and acquire more copyrights.

If creators are acknowledged as holding the copyright to generate AI images, given the difficulty in disproving the “creative process” and “creative time,” individuals with superior computational power may dominate the copyright for images that a model can produce by consistently generating images at random based on diverse parameters, thoroughly examining the potential outcomes.

Because of the uniqueness of the “seed” results and discarding most results that do not meet human aesthetics, the actual available “seeds” may be limited. Ordinary individuals may lose the copyright to an image because of lower hardware computational power and a later generation of available images for that model. This could even lead to consequences such as infringement for using substantially similar images — especially for readers familiar with the current Stable Diffusion software, understanding how small models, especially small LoRA models, have high degrees of similarity and frequency in the final products.

I believe that this presents a future possibility of monopolizing intellectual property rights.

The judge in the verdict considered AI drawing software as a new technological tool, and by correctly applying copyright law, it can encourage more ordinary people to participate in the creative process.

Although the intention is commendable, it clearly only considers the “human” aspect and does not take into account the involvement of the “machine.”

The efficiency of traditional works is only related to the creative ability and efficiency of individuals, and everyone has an equal opportunity to produce works and obtain copyright.

However, the efficiency of producing AI drawing works is significantly linked to the performance of the machine, reaching differences of tens to hundreds of times.

As a personal example, using the flagship home graphics card NVIDIA RTX 4090 with Stable Diffusion can generate one image in one second, while my own graphics card (AMD Radeon RX 5700XT) often takes close to 50 seconds.

If users of AI drawing software are considered to have copyright for the generated images, then this 50-fold difference represents a 50-fold difference in efficiency in obtaining copyright. When using the same model to generate images, individuals with the 4090 graphics card may “draw” usable images earlier, while others have a higher risk of infringement.

This unfair reality should not be the future of copyright in our country.

V. Personal Perspective – Copyright Attribution of Training Sets, Models, and Generated Works in AI Drawing

In light of the new intellectual property disputes arising from AI, I wish to share personal views on the copyright attribution of the three elements in AI drawing.

1. Training Sets

Training sets can be understood as a collection of various artwork images used during model training. I think there are two types: entirely original training sets and those including third-party works.

- An entirely original training set comprises works for which the model creator holds legitimate intellectual property rights. In this case, the copyright of the training set is deemed the exclusive property of the model creator, without infringement on any third-party rights. This point may not require further discussion.

- A training set containing third-party works, as the name suggests, includes works by third parties. In this scenario, the copyright of third-party works belongs to the respective third parties. The compilation of the training set itself (now an assembled work) falls under the ownership of the collector. Moreover, the act of collecting and using this set to train a large model does not violate the rights of third parties, unless the set includes works explicitly prohibited for AI model training by third-party declarations.

The author has previously expressed similar viewpoints (refer to the link in the first half of this article). The training process of AI models, especially using Diffusion algorithms, involves learning various commonalities. Human works’ commonalities are inseparable from shared culture, thoughts, and aesthetics. Even if a work has innovative elements, in an absolute large-scale model, such innovation may appear negligible (as previously analyzed in the article on LoRA model infringement, not reiterated here). The final generated large model will not infringe on the copyright of third-party authors in the training set.

However, I respect each copyright holder’s right to protect their works. Declaring “not for use in AI training” is the right of the copyright holder, and the collector of the training set also has the obligation to respect this right.

2. Models

AI models specifically refer to those trained using a training set and specific algorithms, capable of directly inferring and generating finished AI drawing products.

I believe that the copyright holder of such models is the model creator. However, unless an entirely original training set is used, the copyright holder of the model does not enjoy the copyright of the works generated by the model.

When an entirely original training set is used, it implies that the generated results of the model possess the characteristics of works for which the model copyright holder has copyright. This characteristic, although based on social commonalities, includes more of the copyright holder’s “thought results.” It represents an induction and summary of past “intellectual achievements” and should rightfully be enjoyed by the copyright holder.

When using a training set that includes third-party works, the generated results of the model primarily represent social commonalities. This commonality is not the “thought result” of the model copyright holder but belongs to the collective effort of the training set and, by extension, all of humanity. In such a case, no individual should have the right to exclusively enjoy the copyright represented by a certain social commonality.

3. Copyright of Generated Works

Unless using a model trained on one’s own works, no individual possesses the copyright of AI-direct-generated works.

Directly generated AI works refer to images generated solely by an AI model without any secondary creative input from the user.

I contend that users of AI are mere consumers, not creators of the generated results. All “works” generated by AI, at least currently, are based on mathematical and statistical calculations. Regardless of the user’s intellectual and effort input before generating results, it is merely a process of “continuously attempting to fit different parameters into the formula to achieve better results.”

Consequently, directly generated “works” by AI lack the elements of copyright and should not be protected under copyright law.

However, if a secondary creative process is applied to AI-generated works, including redrawing parts of the image, correcting structural errors, adding more elements, etc., and if the user’s added elements surpass the proportion of the AI-generated work, the user then holds the copyright of the new work.

At this point, the AI work becomes a part of the new work’s material (similar to using reference images in conventional painting), and the user’s “intellectual input” has surpassed the “mechanically generated” portion, meeting the requirements for obtaining copyright.

VI. Conclusion

In this case, the defendant is acknowledged to have directly used the plaintiff’s image, and there is currently no apparent disagreement with this evidence.

However, I contend that, based on the technological principles mentioned in this article, the plaintiff also does not possess the copyright to the images in question. Therefore, the defendant’s actions do not constitute infringement.

Regardless of whether this case qualifies as the “first case by human intervention” as some netizens believe, concerning the new intellectual property issues brought about by AI, it is essential to recognize that legal protection and understanding of intellectual property rights need to align more closely with technological principles.

Facing intellectual property challenges presented by new technologies, we cannot continue to rely solely on past experiences. Instead, we should start from the technical principles, conduct in-depth analyses of the essence of the technology, and combine these insights with the core principles of intellectual property protection to determine whether the technology qualifies for intellectual property rights and whether related actions constitute infringement.

Failing to do so may lead to falling prey to “empiricism” and “subjectivism”.

Attorney at Beijing Long’an (Guangzhou) Law Firm, and Senior Consultant at Long’an Bay Area Artificial Intelligence Legal Research Center. With nearly a decade of experience in internet legal practice, I have provided legal services to internet enterprises listed on the Growth Enterprise Market, among the top 50 internet enterprises in the country, and internet fast-fashion retail unicorns. Specializing in handling litigation and compliance matters for internet-based companies, I excel in utilizing computer technology to deeply excavate evidence.